Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall, built in 1837-1838, was conceived as a meeting place for abolitionists, activists fighting to end slavery. It was meant to host lectures on the importance of the anti-slavery movement, discussions on women’s rights, and other pressing social reforms of the era. However, the building tragically burned down just four days after its grand opening.

This act of vandalism, far from silencing the movement, only fueled it. The burning of the hall sparked outrage among abolitionists, who then continued their fight with renewed vigor. Discover more about the history and significance of Pennsylvania Hall at philadelphia-future.

Abolitionism in Pennsylvania

The movement to abolish slavery, known as abolitionism, spread across the U.S. after the American Revolution. During this time, Pennsylvania emerged as its epicenter. Many active proponents resided here, and the nation’s first abolitionist society was founded in the state. This society played a crucial role in the passage of Pennsylvania’s 1780 law for the gradual abolition of slavery.

In 1794, abolitionist advocates from New York, New Jersey, and Delaware united with Pennsylvania to form the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. By 1829, four of the convention’s meetings had been held in Philadelphia. The city also saw the establishment of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, followed by the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society a year later. In 1837, during the last convention meeting in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society was founded.

Abolitionist activists were highly engaged, and by the 1830s, they began advocating for the complete and immediate abolition of slavery, leaning towards more aggressive tactics. These initiatives sparked negative reactions from some segments of society. Many meeting houses and churches started refusing to rent their premises to abolitionists. In response, abolitionists formed an association to raise funds and construct their own meeting hall. Thus began the story of Pennsylvania Hall.

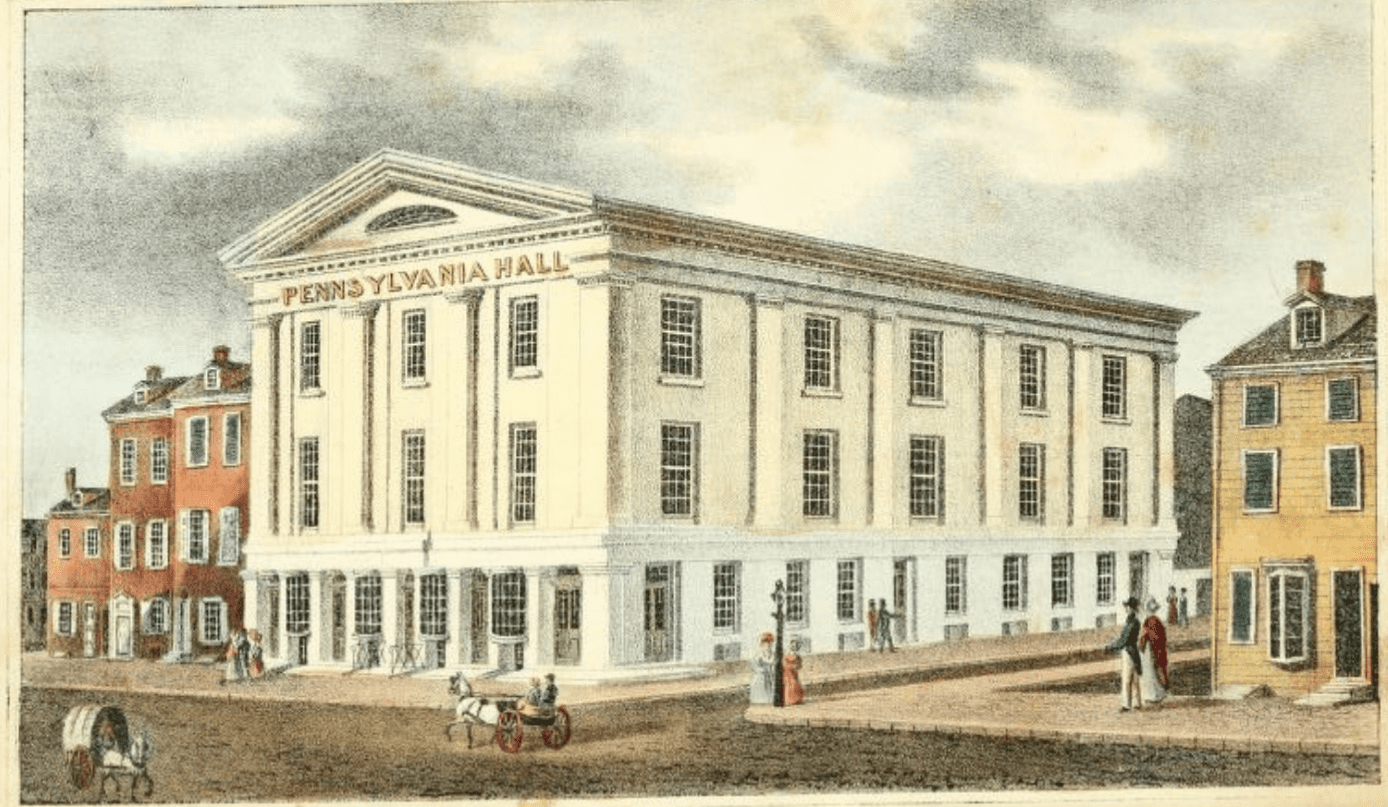

Construction of Pennsylvania Hall

Philadelphia abolitionists played a significant role in fundraising for the meeting hall’s construction. This included both white Quakers, who collaborated with various abolitionist groups across the country, and prominent Black leaders. Within a year, they managed to sell 2,000 shares and accumulate approximately $40,000. Many association members also contributed their own labor and materials to the construction.

The design for the new building was entrusted to architect Thomas Ustick Walter. This marked his first major commission. Construction began in 1837 and culminated in the grand opening on May 14, 1838.

Pennsylvania Hall was erected on Sixth Street with the following layout:

- The first floor housed shops and offices, including an abolitionist reading room and bookstore, the office of the “Pennsylvania Freeman” newspaper, the office of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, and a store selling products made without slave labor. This floor also featured a lecture room for 300 people, two committee rooms, and stairs leading to the second floor.

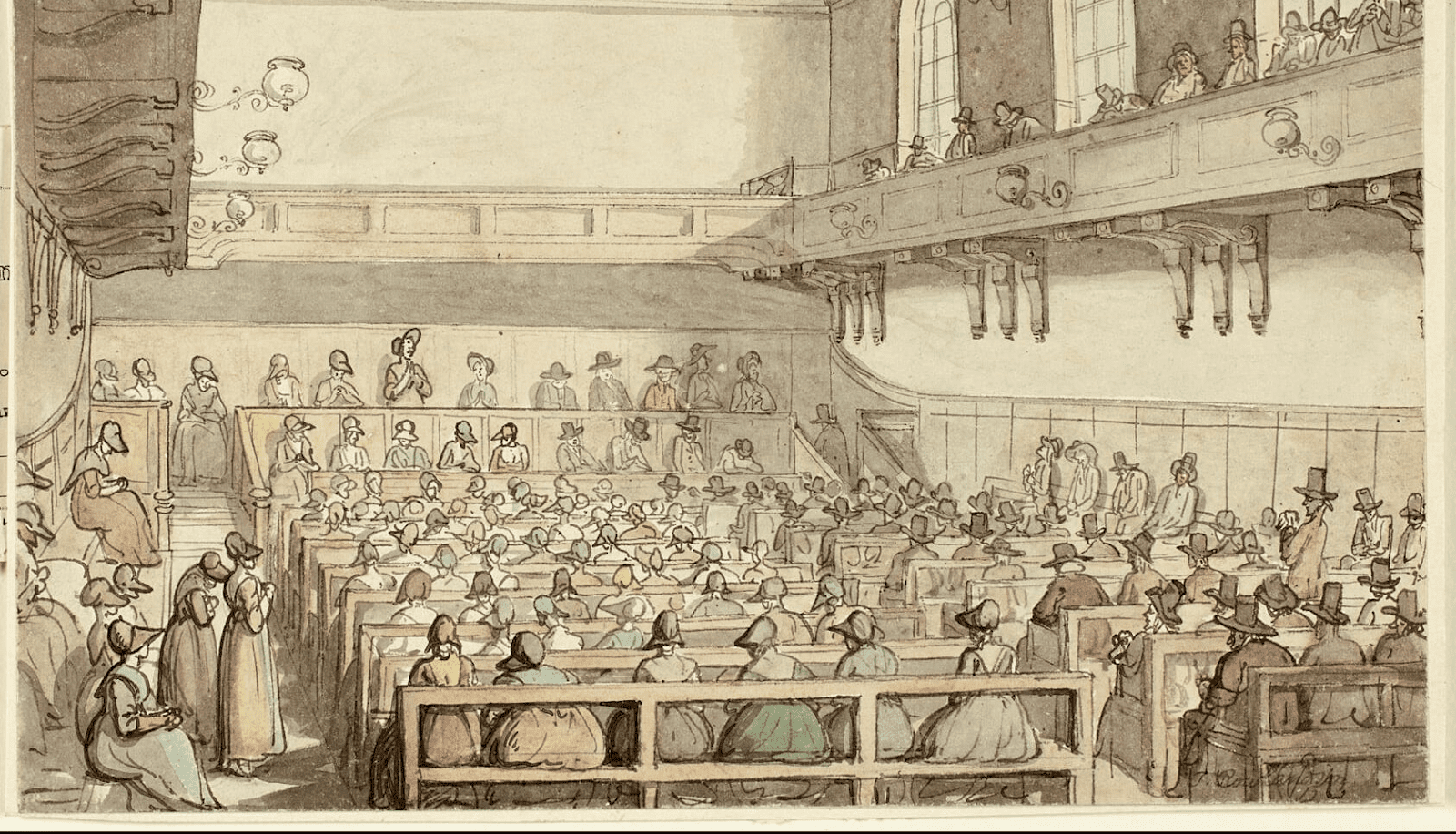

- The second and third floors featured a hall with three galleries, capable of accommodating 3,000 people.

- The basement was planned to house the editorial office of the “National Enquirer and General Register” abolitionist newspaper, but this plan was not realized in time.

The building was ventilated through the roof, and gas lamps provided illumination. The interior decoration was lavish, and above the stage in the meeting hall, Pennsylvania’s motto was proudly displayed: “Virtue, Liberty, and Independence.”

The Building’s Purpose

The new abolitionist building was intended to be a symbolic site with an ideally chosen location. It was deliberately built near Independence Hall, where the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were adopted. It was meant to become a central hub for the Quaker community, which was very active in Philadelphia.

At the time of its construction, abolitionists also aimed to fight for the abolition of capital punishment in the country. Therefore, the building was initially intended to be named “Abolition Hall.” However, even the movement’s representatives deemed such a name too provocative and imprudent. Instead, they settled on the neutral name “Pennsylvania Hall,” genuinely thrilled to finally have their own place for meetings and gatherings.

The Destruction of Pennsylvania Hall and Its Aftermath

The grand opening of the new building took place on May 14, 1838. Philadelphians invited abolitionists from across the Northeastern U.S. They planned a multi-day ceremony that included sessions of the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society and the American Anti-Slavery Convention of Women.

All the aforementioned halls, offices, and the store immediately began operating. Pennsylvania Hall warmly welcomed guests, conducted tours, and commenced meetings according to the planned schedule.

Simultaneously, resistance to the abolitionist movement intensified in Philadelphia. It had been growing throughout Pennsylvania Hall’s construction and reached its peak at the building’s opening. Some Philadelphians blamed abolitionists for the steadily increasing Black population in the city, which they claimed led to job shortages and rising crime rates. When abolitionists gathered in Pennsylvania Hall, rumors began to spread through the city about their alleged improper behavior within the building, as well as calls for racial “amalgamation.”

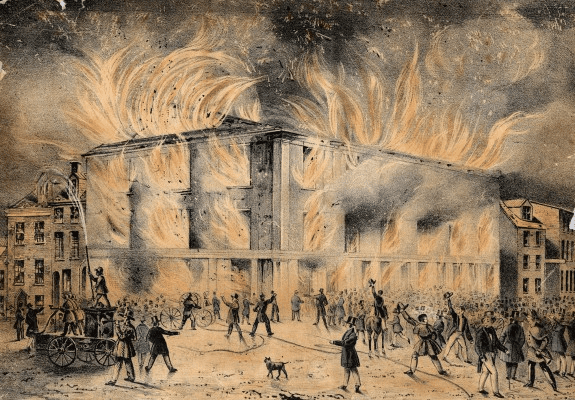

A sizeable crowd gathered around Pennsylvania Hall immediately after its grand opening. On the third day of the conference, when abolitionists discussed the horrors of slavery, people on the street began throwing bricks through the windows.

Mayor John Swift attempted to disperse the crowd, but the attackers’ activity only intensified on May 17, 1838. On this day, they broke down the building’s doors. A mob of white citizens entered and started several fires on the first floor, fueling them with gas from the lighting system. Sheriff John G. Watmough arrested several dozens of rioters, but the crowd immediately freed them. Everyone inside Pennsylvania Hall was forced to evacuate. The fire quickly spread and completely destroyed the building that same night.

Over the next decade, abolitionists actively filed lawsuits to prosecute those responsible for this crime. Dozens of rioters were arrested, but investigations were conducted against only five men, one of whom was eventually convicted. In 1847, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court held the county responsible for the damages. The association was paid $27,942.27.

Although Pennsylvania Hall only stood for four days, it had a significant and lasting impact on the abolitionist movement. People who had previously ignored them or viewed them as a threat to the country began to reconsider their stance. Abolitionists cleverly capitalized on this, arguing that this act of vandalism was directed against liberty in general. Women began making and selling wooden artifacts in memory of Pennsylvania Hall, which helped raise funds for abolitionist activities.

This is how a destroyed building became a symbol of the fight for freedom for both Black and white populations. Abolitionists used this incident to highlight their own contribution to the struggle for freedom and to promote an anti-slavery stance in society, ultimately achieving success.