Philadelphia is the place where the key documents of American history were signed, but before those words made it onto parchment, they had to be printed. The story of the printing industry in this city is more than just a chronicle of technological development; it’s a critical narrative of how paper and ink became the most potent weapon in the fight for liberty.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Benjamin Franklin and his successors, Philadelphia evolved into the intellectual hub of the colonies. It was here that Enlightenment ideas took root and the first calls for independence were published. We explore how printing presses transformed a colonial town into a crucible of radical thought, and why it was Philadelphia’s publications that shaped the consciousness of a nation preparing for revolution, over at philadelphia-future.com.

Forging the Paper Industry

The center of Pennsylvania during the colonial era wasn’t just the largest city; it was the true intellectual and publishing epicenter. It was on this foundation of freedom and enterprise that the printing industry flourished, becoming the bedrock for the formation of independent American thought.

The establishment of printing in the region is closely tied to the development of paper manufacturing. Although the printing press was imported from Europe, mass-producing books and newspapers required a local raw material source. In 1690, the first paper mill in the colonies was opened near Philadelphia. This fact points to the deep entrepreneurship of the early settlers, who understood a simple yet defining truth: disseminating knowledge and information requires a robust manufacturing base. The availability of quality local paper ensured stable, import-independent growth for the printing trade.

Architect of the Information Space

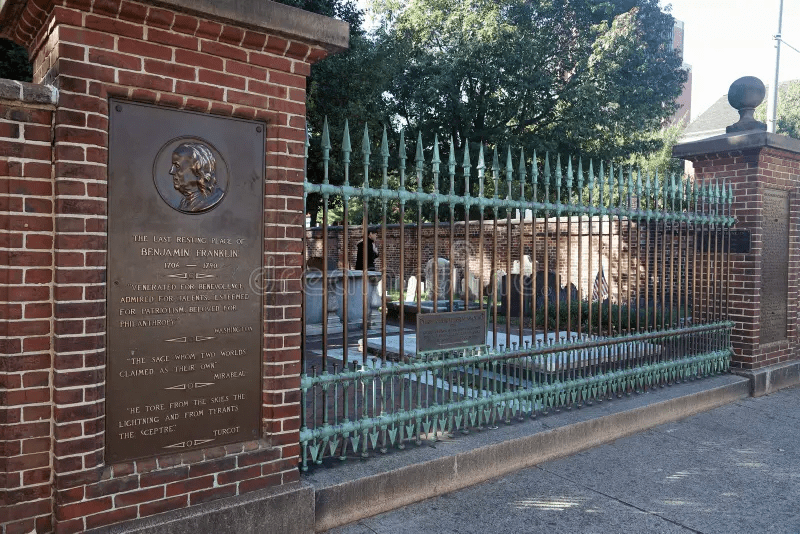

It’s impossible to discuss printing in Philadelphia without mentioning Benjamin Franklin. He was far more than just a printer. This politician was an outstanding statesman, inventor, and the architect of the American information space. Franklin began his journey in the field in 1727 by founding his printing house. He quickly transformed it into the city’s center for intellectual life.

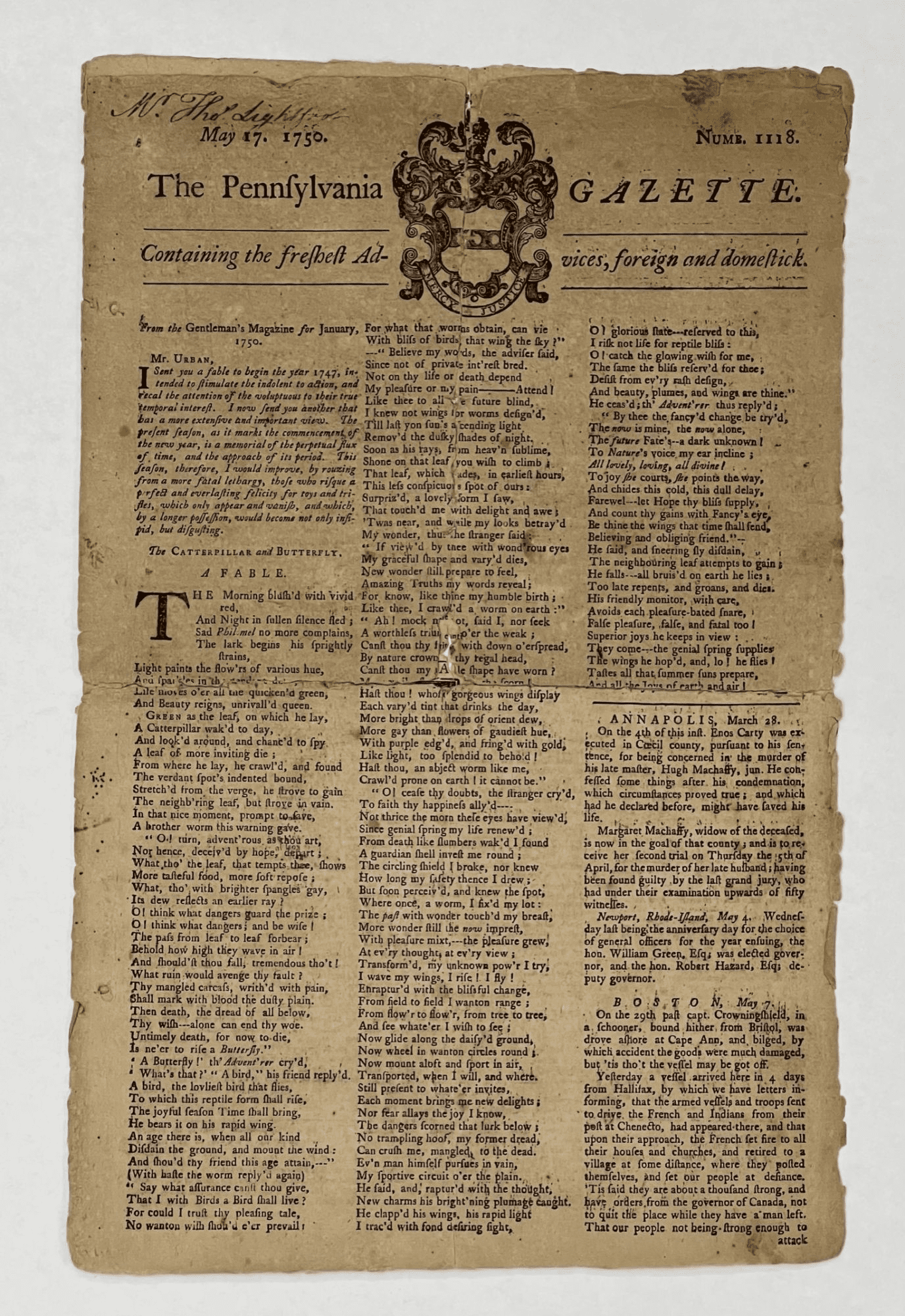

- The Pennsylvania Gazette. Franklin was the publisher of this newspaper from 1729 to 1748. He turned it into one of the most influential and successful colonial publications, using it to spread news, essays, and political satire.

- Poor Richard’s Almanack. Franklin gained widespread popularity through these annual almanacs. They contained not only astronomical data but also practical advice, humor, and wise maxims like “Time is money.” The Almanack became a bestseller, illustrating how deeply printing was integrated into commercial and public life.

- Founding the First Public Library. In 1731, Franklin established the Library Company of Philadelphia. This was the first subscription-based library in the colonies. This move expanded access to the printed word for the middle class, which was revolutionary for the proliferation of knowledge and critical thinking.

- Spreading a Network of Print Shops. Using his connections, Franklin created a de facto network of franchises or partnerships. He helped establish new print shops and newspapers in other colonies (including New York, Charleston, and Jamaica), providing them with equipment and training staff. This made him the leader in printing across all of Colonial America.

Benjamin Franklin’s example brilliantly illustrates how the printing trade became an integral part of the commercial and political fabric of the American colonies. His print shop functioned as a true center for information and even financial management. He wasn’t limited to just publishing literary works or newspapers. He handled government commissions, from printing legislative acts to publishing intercolonial agreements.

His involvement in the currency sphere was particularly significant. Franklin was actively involved in producing colonial paper banknotes. Recognizing the threat of counterfeiting, he showed ingenuity by developing unique security features. To achieve this, he created a special ink composition, adding graphite, and used complex printing plates. This was more than just a technological innovation; it was a strategic measure that secured trust in the colonial currency.

However, his most significant achievement was the management of public opinion. Franklin used his press, especially The Pennsylvania Gazette, as an effective means of shaping a unified viewpoint. His publications and essays raised the educational level of the populace, which, in turn, fostered the ideological cohesion of the colonies. He effectively transformed the printing press into a powerful tool for political mobilization, playing a critical role in the period immediately preceding the armed struggle for independence.

Early Newspapers and the Rise of Journalism

Periodicals became the driving force of communication, turning the city into a hub for the exchange of ideas. Philadelphia’s newspapers quickly surpassed those in other colonies in influence.

- They didn’t just report local news and announcements.

- Newspaper columns served as a platform for political debate and the publication of pamphlets.

- The publications contributed to the rising literacy rates among the population.

These printed sheets became the means that united the disparate colonies, helping people feel part of a shared intellectual community preparing for the fight for self-determination.

The Instrument of Revolution

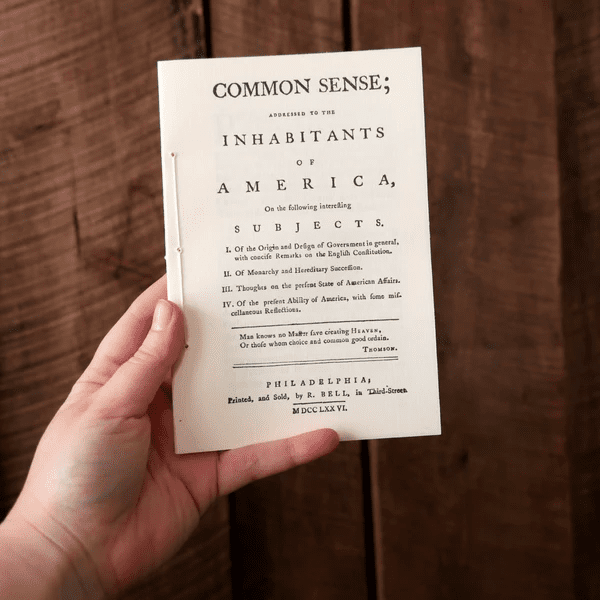

Philadelphia’s printing activities took on special weight during the American Revolution. The city’s presses printed most of the political pamphlets and declarations that fueled the spirit of resistance against British rule.

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense—one of the most influential printed works of that period, calling for a break with England—was printed right here. Thanks to the established network of print shops, the ideas of independence spread with a speed unimaginable in the previous era. The city became not just the place where the Declaration of Independence was born, but the center that ensured its immediate communication to all corners of the continent.

The Symbiosis of Print and Education

A crucial component of Philadelphia’s printing success was its close collaboration with educational and scientific circles. Franklin was not only a printer but also the founder of the American Philosophical Society. This institution, which grew out of his discussion group of artisans and merchants, actively used print to disseminate scientific discoveries, treatises, and academic works. Thus, the printing industry ensured a constant flow of knowledge, transforming Philadelphia into the capital of American Enlightenment.

Below is a chronological table of printing development in the City of Brotherly Love.

| Year / Period | Key Event | Significance for the Region |

| 1690 | Founding of the first paper mill near the city. | Ensuring an independent raw material base for mass production. |

| 1727 | Benjamin Franklin establishes his own printing house. | Beginning the era of commercially successful and influential printing. |

| 1729 | Publication of The Pennsylvania Gazette begins. | Shaping quality journalism and political discourse. |

| 1732–1758 | Publication of Poor Richard’s Almanack. | Spreading Enlightenment ideas and practical knowledge among the public. |

| 1776 | Mass printing of revolutionary pamphlets and the Declaration. | Printing as a direct instrument of the American Revolution. |