As the 19th century turned into the 20th, Philadelphia was rapidly growing into Pennsylvania’s largest city. Its horse-drawn omnibuses and electric streetcars could no longer handle the frantic pace of life. The city, which had served as the cradle of American democracy, urgently needed a new, high-speed artery: a subway system.

The history of the Philadelphia subway is a unique saga of ambition, engineering challenges, and, notably, private enterprise. Unlike New York City, the first lines were constructed without direct government funding. Launched in 1907, the Market Street Elevated was a revolutionary hybrid. It dipped underground in the city center and rose onto elevated tracks in the western districts. This system not only relieved street congestion but also determined the direction of the city’s territorial and demographic growth. We delve deeper at philadelphia-future.com into how this “iron odyssey” shaped modern Philadelphia and why its subway remains a living monument to the engineering spirit of that era.

The Birth of the “El”

The initiative to create a high-speed urban transit system was actively discussed following the success of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. However, these plans only became a reality at the start of the 20th century. On March 4, 1907, the first segment of the line now known as the Market–Frankford Line (MFL), or simply the “El” (from Elevated), was opened.

This branch was a true engineering marvel of its time. It combined an underground section beneath Market Street in Center City with an elevated structure to the west. Interestingly, the construction of this initial line was financed by private capital from the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, without significant government investment—a rarity for many American subway systems. The launch of this major route spurred active residential development in West Philadelphia.

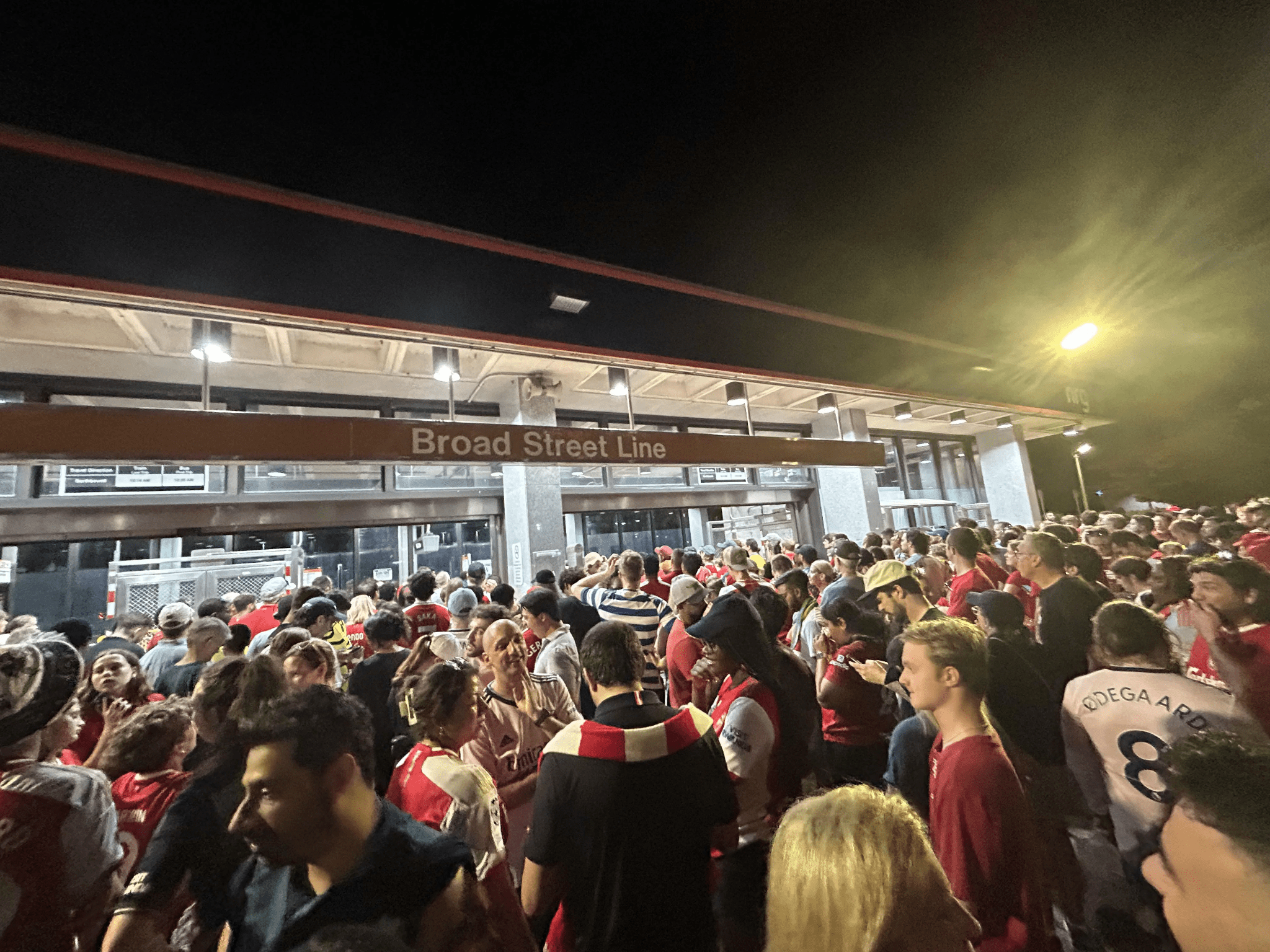

The City’s Underground Spine

The second major branch, the Broad Street Line (BSL), or the “Orange Line,” emerged later and involved a different construction approach. Planning began around 1912, but it did not open until September 1, 1928. Unlike the first line, the BSL was built almost entirely underground, running directly beneath the wide Broad Street Avenue.

It was envisioned as Philadelphia’s primary transit corridor, designed to serve residents in the northern and southern outskirts. Initial BSL plans included a four-track tunnel along a significant portion of the route. This design allowed express trains to bypass local services. Such an ambitious project underscored the foresight of the engineers, who anticipated substantial growth in ridership.

Engineering Distinctions

The Philadelphia subway is notable for a diversity of track gauges that is unusual for the U.S. While most lines use the standard gauge, the Market–Frankford Line features a wider, Pennsylvania streetcar gauge (1581 mm, or 5 ft 2 1⁄4 in). This is a relic of the older streetcar network.

Constructing the underground section of the Broad Street Line required complex work due to the dense urban environment. For instance, in some central areas, tunnels had to be laid close to the foundations of historic buildings. Elevated structures are also an integral part of the system, particularly on the northern and eastern sections of the MFL, allowing trains to move quickly above city vehicular traffic.

A Network of Transit Autonomy

Philadelphia’s underground transit functions as part of a much larger and more complex system, culminating in the creation of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA).

Since the late 1960s, SEPTA has transformed the fragmented private and municipal networks (buses, trolleys, subways) into a single, integrated transit system. This consolidation was vital for ensuring effective mobility throughout the city and its densely populated suburbs. SEPTA currently manages both of Philadelphia’s subway arteries.

The Philadelphia subway network is functionally complemented by the PATCO Speedline (Port Authority Transit Corporation). This line, opened in the late 1960s, is unique and plays a critical interstate role. While technically not part of the local subway, the “Speedline” strategically crosses the Delaware River, providing a crucial link between Center City Philadelphia and cities in southern New Jersey, notably Camden and Lindenwold. This strategic extension transformed Philadelphia into a true regional hub, significantly easing the daily commute for thousands of residents who cross state lines. Thus, Philadelphia built not just a local subway, but a powerful cross-border transit corridor that effectively fuels the economy of the entire region.

Development and Reconstruction

Following the initial wave of expansion in the 1920s and 1930s, the next major phase of development occurred in the post-war period and beyond.

- In the 1950s, some elevated sections of the MFL were demolished, and the lines were relocated to new subway tunnels.

- In 1973, the Broad Street Line was extended south to the Pattison station to serve the recently constructed city sports complex.

- From the late 1980s to the early 2000s, both major branches underwent phased reconstruction aimed at improving infrastructure and enhancing passenger safety.

These updates have allowed the system, despite its age, to remain the busiest component of the local transit network.

A New Era — New Challenges

After 2000, the Philadelphia subway, managed by SEPTA, entered a phase of comprehensive modernization focused on improving reliability and passenger comfort, rather than large-scale expansion. The main focus was on updating the rolling stock. New cars were introduced on key lines, significantly improving energy efficiency and reducing operating costs. Modern fare collection systems were also implemented, notably the contactless SEPTA Key card. This innovation streamlined access to the network and integration with other modes of urban transport. Significant investments were also directed toward repairing stations, some of which have been operational for over a century.

In the 21st century, the system faces challenges typical of American metropolises: the need to balance rising operating costs with the demand for affordable fares. Furthermore, the load on key lines has increased, requiring continuous solutions to maintain capacity without building new, extraordinarily expensive tunnels. SEPTA is actively working on projects aimed at creating a barrier-free environment for people with disabilities at all stations.

The Resilience of the Underground City

The history of the Philadelphia subway is a monumental testament to how a city can use infrastructure as a tool for transformation. Born in the era of private initiative and the “War of the Currents,” this underground and elevated system has become an inseparable part of Philadelphia’s identity and economic viability.

Today, under SEPTA’s management, the network continues its mission: maintaining mobility, reducing road congestion, and connecting people—both within the city and to neighboring New Jersey via PATCO. Despite the challenges of aging infrastructure, the Philadelphia subway remains a critically important element of the region’s resilience, having successfully navigated the city through two centuries of economic and social change. Its existence is a constant reminder of the power of engineering heritage and its ability to shape the future of urban life.