Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, a beekeeper, clergyman, and teacher, was a towering figure among American apiarists and even served as the president of the U.S. Beekeepers’ Union. He’s rightfully known as the “Father of American Beekeeping” and the inventor of the “bee space”. But do you know why? Find out more at philadelphia-future.

A Childhood Fascination with Insects

The future “Father of American Beekeeping,” Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, was born on December 25, 1810, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. From a young age, he was deeply fascinated by insects and their behavior. His educated and well-off parents didn’t approve, often punishing him for the worn-out knees of his trousers from constantly observing ants.

In 1827, Lorenzo enrolled in Yale College, graduating in 1831. His father, unfortunately, lost his fortune, leaving Lorenzo to earn his own living. From 1834 to 1836, he taught mathematics at Yale while also studying theology. Afterward, Langstroth became a pastor, serving in several churches across Massachusetts.

In 1848, Lorenzo served as a pastor in Greenfield, Massachusetts, and also took charge of a school for young ladies in the same town. However, his health soon declined. Lorenzo left his ministry and moved to Philadelphia, where he opened a women’s educational institution.

It was during this period that the future famous beekeeper became seriously interested in bees. It’s said that Lorenzo decided to keep bees as a form of therapy to alleviate severe bouts of depression. One day, Lorenzo visited a friend’s apiary and was captivated by the rich and somewhat mysterious life of bees. Due to his frequent illnesses, Langstroth eventually had to give up teaching, and that’s when beekeeping truly took center stage in his life.

In that same fateful year, 1848, Lorenzo first encountered the works of renowned bee researchers F. Huber and Dr. Bevan. It was they, as Lorenzo Langstroth later noted, who opened his path to beekeeping literature. Inspired, Lorenzo acquired F. Huber’s “leaf-hive” and several other linear hives, beginning his research into various hive designs. Notably, François Huber constructed his “leaf-hive” in Switzerland in 1789. This hive featured fully movable frames that attached to one another, forming a box when fully assembled. When the beekeeper unfolded the combs, the hive resembled a book. Langstroth wrote that Huber’s hive would have fully satisfied him, but only if certain precautions were observed:

“…the combs should be removable so as not to irritate the bees, thus allowing the insects to be tamed to an incredible degree. Without acknowledging these facts, I must consider a hive that does not allow the combs to be removed as quite dangerous for practical application.”

The Invention of the “Bee Space”

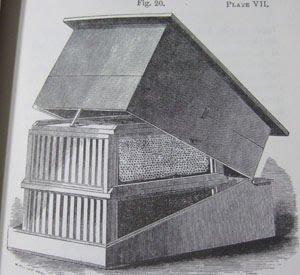

In October 1851, Langstroth created his own hive design. Its primary feature was movable frames whose shoulders rested on the hive walls. The distance between the frames, and between them and the hive body, was ⅜ inch (about 9 mm). The inventor’s ingenious idea was based on the discovery that bees never build combs in such narrow gaps. If the space was slightly larger, bees would build combs, but if it was smaller, they would fill the gaps with propolis.

Today, the “revolutionary” distance within a bee colony, which Langstroth once spoke of, is known as “bee space”. While movable frames and various hives allowing bees to develop comfortably existed before Langstroth, “uncontrolled” bees made inspecting their colonies significantly difficult for every beekeeper. Langstroth offered a new solution to this problem (at least he was definitely the first in the U.S., as this method was already used in Europe). As a result, bees no longer “glued” the frames to each other or to the hive body, meaning beekeepers didn’t have to destroy these structures during inspection. Furthermore, the frames in the inventor’s hive could be removed from above and freely moved without damaging the combs, which also eased the beekeeper’s work. On the day of his invention, Lorenzo noted in his notebook that he was confident the use of movable frames would give new impetus to beekeeping, facilitate bee breeding, and increase their profitability. Also, a few months before the aforementioned invention, Langstroth so perfected the linear hive that he could easily divide swarms and obtain commercial honey. To make honey extraction even easier, he made the bottom removable.

Langstroth’s Hive – The Ancestor of Modern Hives

Langstroth’s hive became the precursor to the popular multi-story Langstroth-Root and Dadant-Blatt hives used in amateur and commercial production today. It’s said that all “long hives” originated from his design. Lorenzo described the advantages of his invention:

“…the main feature of my hive is the ease with which the frames could be moved without angering the bees… I was able to combat natural swarming and at the same time learned to multiply colonies with ease, speed, and greater certainty than by methods then in use… Weak colonies could be strengthened, and those that lost their queen could raise a new one thanks to this system… If I suspected something was wrong with a bee colony, I could quickly check its condition and apply the necessary treatment.”

On October 5, 1852, Langstroth received a patent for his first movable frame hive in America. Henry Bourquin, a carpenter from Philadelphia, Langstroth’s colleague and a beekeeping enthusiast, built the first hives for him. Their number exceeded a hundred that year, and the inventor sold them wherever he could. However, it’s said that for a long time he struggled to protect his patent, as other claimants sought to preempt him. Essentially, Langstroth was doing the same work as the prominent Polish beekeeper Jan Dzierżon and the Ukrainian Petro Prokopovych. Yet, Lorenzo was unaware of the inventions of these and other progressive colleagues at the time. Regardless, his name stands at the forefront among the founders of commercial industrial rational beekeeping. For over 150 years, Langstroth’s improved hive has been used by beekeepers worldwide. In the U.S. and Canada, 95% of commercial apiaries have chosen his design.

Other Discoveries by the Inventor

Lorenzo Langstroth made other discoveries in beekeeping that are still applied today. For example, he discovered that several adjacent hive bodies could be stacked one on top of another. And the queen could be isolated in the bottom or brood chambers. Then the upper chambers would be at the disposal of worker bees and consist only of honeycombs. This simplified hive inspection, bee colony management, and contributed to the transformation of beekeeping into an industrial sector. In Langstroth’s time, honey was the primary sweetener in the American diet, and his methods proved very timely. Beekeeping was able to operate profitably on a large industrial scale. Under these conditions, the reuse of empty combs was also “advantageous,” significantly impacting the amount of honey produced. Because to produce just 1 kg of wax for combs, a bee needs to consume up to 4 kg of honey! And the gentle honey harvesting in Langstroth’s hives (without destroying nests or harming bees) contributed to the formation of strong, healthy colonies in apiaries.

A Book Popular for Over a Century and a Half

Langstroth authored the book “The Hive and the Honey-Bee” (first edition 1852). It has been translated into numerous foreign languages, reprinted at least 40 times, and is still being republished today because it remains relevant.

It’s called a fundamental work on beekeeping, a beekeeper’s bible, and a practical guide on how to start beekeeping from scratch. The book is written in accessible language. It not only provides instructions on how to set up an apiary “from nothing” but also how to craft the necessary tools yourself. The publication contains a wealth of other interesting and detailed information, including the life of honey bees, their hierarchical relationships, and how to protect bees from various ailments. The author also described his own hive invention.

Later Years: Without Bees and Without Money

In 1858, Langstroth established an apiary of his hives in Philadelphia and began selling them. That same year, he moved to Oxford, Ohio, choosing an ideal location for his apiary.

Langstroth was one of the first to take an interest in Italian bees and facilitated their importation into the U.S. in 1863. They were more productive than the European bees, which were then most common in the U.S. Langstroth and his son sold Italian queen bees for $20 each, selling over 100 in their most successful year, shipping them by mail across the country.

Near the apiary, Lorenzo planted linden and apple trees, and he dedicated a section as a “honey garden” where buckwheat and clover bloomed for the bees. The house where the famous beekeeper lived is now called the Langstroth Cottage and is a National Historic Landmark.

In 1874, the death of his son and his own ailments forced the beekeeper to sell his apiary. He received relatively little money for his inventions. The patent on his hive expired by the time beekeeping became an industrial sector. And the man whose hives would later be favored by millions of beekeepers worldwide died… a poor man. This occurred in 1895 in Ohio, where the inventor lived with his daughter’s family. The “Father of American Beekeeping” passed away during a sermon about God’s love in a church in Dayton and was buried in the city’s cemetery.

The epitaph on his tombstone reads:

“In Memory of L.L. Langstroth, “The Father of American Beekeeping,” his loving admirers, in honor of his constant and persistent observations and experiments on the honey bee, improvements in hive construction, and literary ability, demonstrated in the first popular scientific book about beekeeping in the USA, gratefully erect this monument.”