Philadelphia, famously known as the cradle of American democracy and a city founded on the principles of Quaker restraint, always had two faces. Behind the façade of strict morality and historical dignity, a hidden economy of sin flourished for a century.

Below on philadelphia-future, we discuss not just a shadow business, but a complex social and urban phenomenon. How and why did entire districts of “priestesses of love” emerge in a city dominated by strict religious laws? What secrets did the elegant elite meeting salons and the simple working-class shelters hide? And most importantly: how did this industry become an integral part of the city’s economy, thriving thanks to corrupt pacts with the police, before being destroyed by a great crusade of social reformers? This is a deep dive into the forgotten chronicles of Philadelphia, where high politics met human weakness.

The Birth of the “Tenderloin”

Before diving into the forbidden corners of Philadelphia, where shadow commerce thrived against a backdrop of Quaker piety, it is important to understand where the history of this indecent, yet integral, element of urban life began. It all started with the Philadelphia district nicknamed “Tenderloin.” It emerged and solidified during the rapid industrialization of the second half of the 19th century.

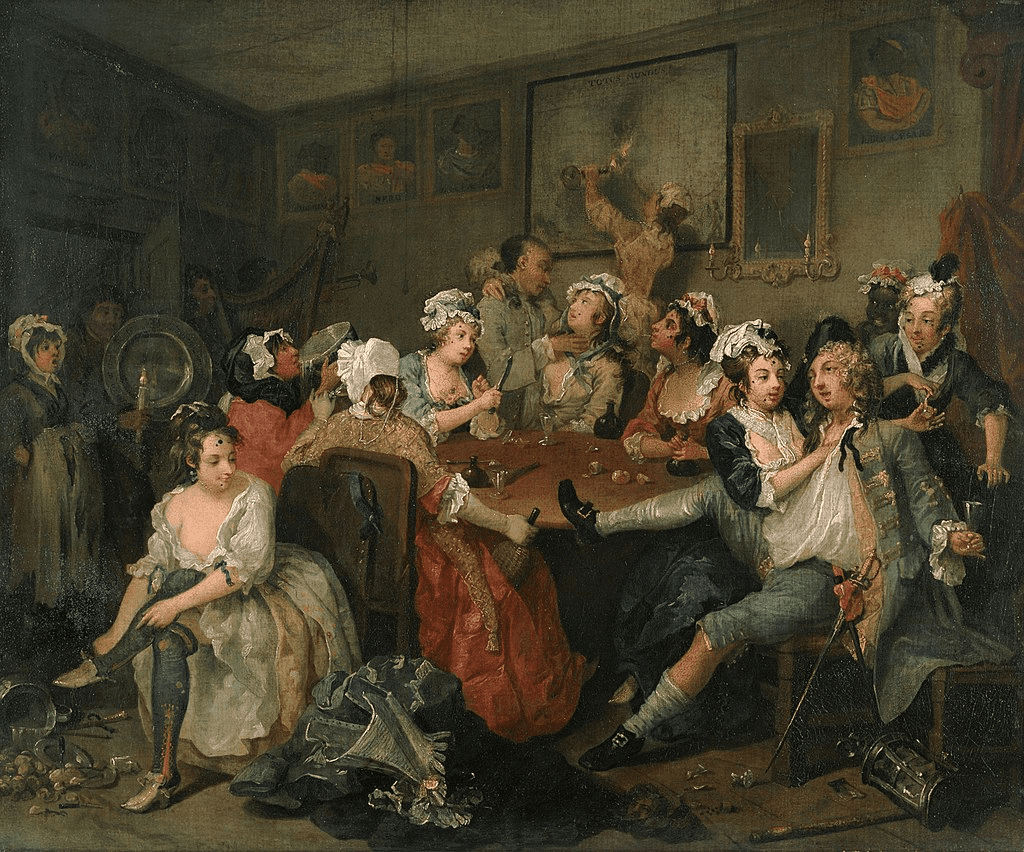

Like its counterparts in New York or Chicago, this location was not officially defined but represented a territorial formation around Seventh and Eighth Streets south of Center City. The rapid influx of immigrants, the growth of the working population, and a lack of social institutions created an ideal ground for the shadow business to flourish. Premises quickly converted from ordinary residential apartments into closed clubs and dens were located near the industrial quarters and port docks. This ensured a steady stream of customers—primarily sailors, dock workers, and even wealthy businessmen seeking anonymity.

It was here that the hierarchy of establishments formed: from dives where services could be purchased for pennies to expensive, lavish salons catering to the city’s financial elite. The interaction between these venues and official institutions was key. Ensuring the smooth operation of such a network required a complex system of agreements and informal coordination. No such center could exist without “protection” and guarantees of complete safety from municipal law enforcement.

The Economy and the Underground Power

The activities of these vice establishments were inseparable from a large-scale corruption network. In fact, the shadow profit from this service segment served as a reliable source of income for many representatives of the city administration, and especially the police force. Control over the area was maintained through a complex system of bribes and kickbacks, known as “protection money”. Monthly payments guaranteed the establishment’s not just tolerance, but complete immunity from raids and prosecution.

Documents and historical evidence from the late 19th century indicate that every patrolman and officer working in the area received unofficial supplements to their pay. This created a parallel governance structure where the real power belonged not to the mayor’s office, but to those controlling the flow of illegal finance. Among the most famous figures who supported this system were the so-called “kings of vice”—local leaders who acted as intermediaries between house owners and officials. This financial scheme was so embedded in the city’s economy that any attempt by reformers to break this vicious cycle instantly met with fierce resistance and sabotage. A 1913 morality commission report detailed that bribery flourished even among the highest ranks.

The Political “Shield”

Control over Philadelphia’s successful illegal business was inextricably linked to the top of the city’s political structure. Concentrated in the hands of the Republican Party leaders, who absolutely dominated the region, this shadow sector functioned thanks to powerful political patronage.

One of the most influential figures behind this corrupt machine was William “Bill” S. Vare. Vare and his brothers, Edwin and George, led Philadelphia’s most powerful political machine at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Although Vare did not directly participate in pimping or managing the establishments, his political organization was the unbreakable “shield” that allowed this industry to flourish without any interference.

The system was complex and effective:

- Police Protection. The police, who were directly subordinate to Vare’s party machine, guaranteed owners of illegal establishments complete immunity from raids and legal prosecution.

- Financial Scheme. In return, brothel owners were obliged to regularly pay a corrupt levy and ensure guaranteed votes in elections, which strengthened the Republican Party’s power.

- Flow of Corruption. Financial streams flowed upwards through a network of ward captains—local political leaders who collected the “tax” on the ground.

Thus, Vare received a dual benefit: constant financial sustenance for his machine and political loyalty ensured by the prosperity of “vice.” This system made him one of the main indirect patrons of prostitution in Philadelphia, embedding the illegal business into the very foundation of city governance.

Fates Behind the Scenes

The lives of the women who worked in these entertainment venues rarely made it into official chronicles and were often linked to social ostracism and destitution. While the outward glamour of some premium salons might create an illusion of comfort, the vast majority of workers were financially dependent on owners and pimps. Many were young immigrants or daughters of poor laborers, for whom this sector was the only path to ensure their survival in the big city. Historical records indicate that a significant portion of their earnings went to paying for lodging, food, and “protection,” leaving them with minimal funds.

A notable figure was Mary “Mother” Dean, an influential owner of a network of houses who managed to build her own independent financial empire. She is known as one of the few women who gained significant power in this shadow world, despite the general male dominance.

List of issues faced by the workers:

- Class Stigmatization. Women in this profession were completely excluded from respectable society.

- Lack of Medical Care. Sanitary conditions were appalling, and access to qualified medicine was almost impossible.

- Financial Exploitation. Almost total lack of control over their earnings.

However, even her influence could not protect the industry from inevitable changes. Social reformers at the turn of the century sought not only to eliminate this business, but also to provide opportunities for the rehabilitation of women. Although, this process was extremely difficult and prolonged due to the deep social isolation of these workers.

The Crusade: Liquidation and Legacy

From the beginning of the 20th century, public tolerance for visible centers of vice began to decline rapidly. This was fueled by the activity of the Progressive movement and the activation of religious and moral organizations, which launched a genuine crusade against organized prostitution. A decisive moment was the creation of the Commission of Morality in the early 1910s, which received broad powers for investigation. The collected testimonies about the spread of venereal diseases, the ties between criminal structures and the police, and the exploitation of minors caused significant public outcry.

Under pressure from the public and federal structures, the city authorities were forced to take decisive action. A series of large-scale raids was conducted, and many famous establishments that had operated for decades were permanently closed. The “Tenderloin” district, as a single, compact center of illegal activity, ceased to exist.

This liquidation did not eradicate prostitution but forced it to disperse into smaller, less noticeable clusters throughout Philadelphia, shifting it into an even more hidden format. Documents from the late 1910s record a sharp decline in the number of large brothels, indicating the success of the reform efforts in changing the urban landscape and reducing the influence of organized crime on law enforcement. The legacy of this struggle left a deep mark on the structure of municipal control and local self-governance.

Historical Perspective

The story of the prosperity of shadow leisure centers in Philadelphia is a vivid example of the complex interaction between economic needs, corruption in the administration, and social reform. These establishments were not merely centers of sin; they were social and economic indicators reflecting acute problems: migration processes, class inequality, and the lack of real opportunities for women from lower strata. Although the physical buildings were demolished and the area cleaned up, the lessons of this era still serve as an important source of knowledge about the past of city governance and the paths to its moral purification.