In the late 19th century, a notorious criminal district emerged in North Philadelphia, earning itself the infamous nickname “The Tenderloin.” Bounded by 6th Street to the east, 13th Street to the west, Race Street to the south, and Callowhill Street to the north, this area was a hotbed of cheap entertainment, gambling dens, saloons, opium haunts, and brothels. All the while, the police seemed utterly incapable of curbing the pervasive corruption and criminal underworld. Let’s delve deeper into the rise and fall of this notorious neighborhood. Read on at philadelphia-future.

Population and Entertainment in Philadelphia’s Tenderloin District

Philadelphia’s Tenderloin district sprang up on the edge of the city’s central business district, close to the new railway stations. This area was once primarily home to merchants, but as the city grew, many moved to other neighborhoods. The former suburban area they left behind consisted of apartments and single-family homes, interspersed with shops and warehouses, all with relatively low housing costs.

These conditions made it an attractive destination for the working class, impoverished African Americans, and immigrants from Europe and China. Gradually, the neighborhood saw an increasing number of homeless residents, and local cheap restaurants and buffets catered to them. The cheap entertainment industry also began to flourish:

- Between 1875 and 1895, three vaudeville theaters operated here.

- By 1910, the district boasted five movie theaters.

- Shooting ranges and various live shows also drew crowds.

The neighborhood’s marginalization deepened with the widespread abuse of cocaine, opium, and morphine. By 1910, annual opium consumption in the U.S. reached approximately 68,000 pounds. Drug trafficking was most active in the Chinese quarters. This was largely due to opium smoking being a tradition in China, which immigrants brought with them to the New World.

The Tenderloin became part of Philadelphia’s Chinatown, and opium dens thrived. This illicit business wasn’t limited to Chinese residents; Americans and African Americans, both men and women, also got involved. Simultaneously, more and more brothels emerged, further worsening the neighborhood’s reputation and attracting a growing number of criminals.

Social Vice and the Police

Police attempted to curb illegal activities in the Tenderloin. However, in the early 20th century, the Philadelphia press began to report that criminals, brothel owners, and opium den operators were colluding with police officers, who regularly accepted bribes and turned a blind eye to their actions.

In 1905, the “Philadelphia Inquirer” published a major article by Reverend Daniel I. McDermott, who meticulously detailed the vices in the Tenderloin and the apparent complicity of the police, city hall, and the ruling Republican party.

All those eager for change rallied around Rudolph Blankenburg. He became Philadelphia’s mayor in 1911 and launched a major reform campaign. He established a commission that uncovered the intricate details of Philadelphia’s thriving markets for drug use, gambling, and commercial sex. The Tenderloin district was, without a doubt, the most active zone for these illicit activities.

In the mayor’s view, these vices were a true social ill that required “treatment” akin to severe diseases. Other proposals included either complete eradication or regulation and licensing. Rudolph Blankenburg decided to “treat” the Tenderloin because it was surrounded by other city neighborhoods. Ordinary citizens lived there and were forced to cross these streets on their way to work or the city center.

Thus, the Tenderloin became subject to regular police raids and missionary moralization efforts. Religious reformers arrived with sermons, and Mayor Blankenburg even led a walking tour of the Tenderloin. In 1912, he declared the city’s vices eradicated, but police continued to make arrests and still documented much illegal activity in that part of the city.

Changes in the Tenderloin District

Brothels in the Tenderloin district began to decline from 1920 onwards. When the U.S. joined World War I in 1917, many state-level changes were introduced to suppress vice and promote healthier lifestyles, especially among servicemen.

Police increased their control over the Tenderloin, and criminals started seeking new locations. Further shifts in gender dynamics, new economic opportunities, and a federal apparatus of prohibitions and penalties ultimately changed the landscape of vice. The culture of alcohol and drug abuse gradually faded away.

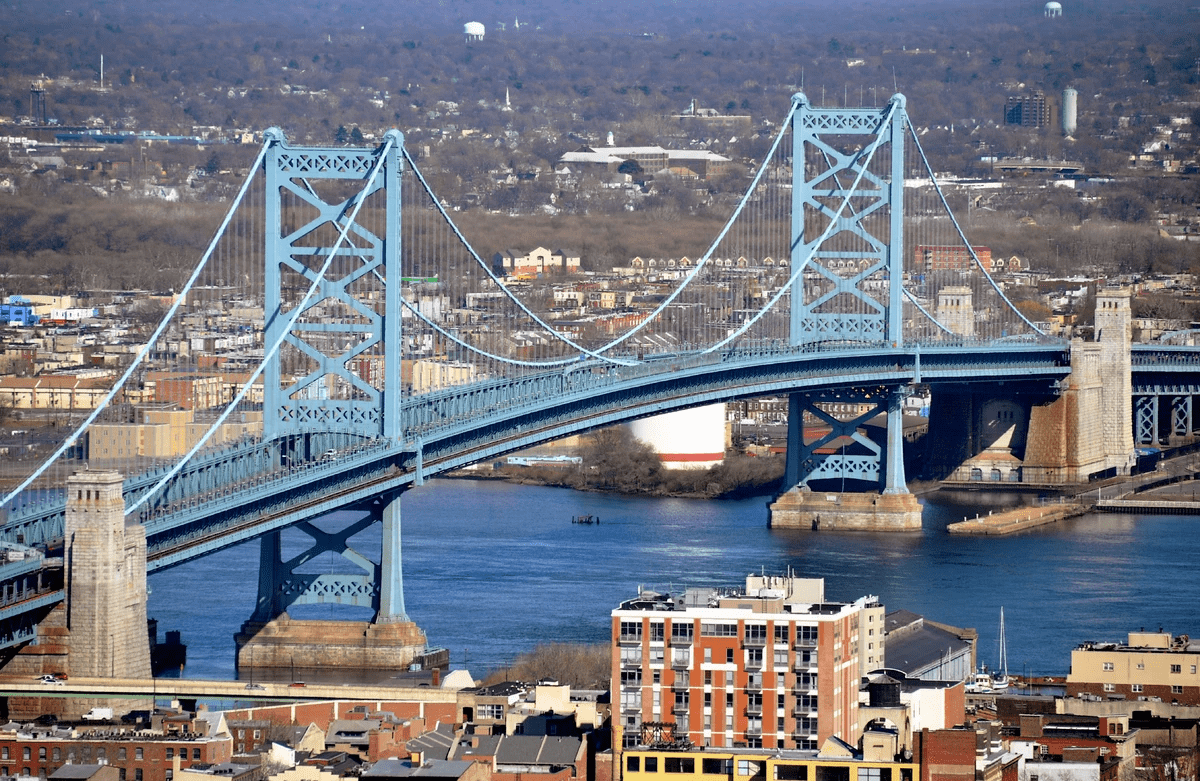

The district was further transformed by architectural changes. In 1926, the Delaware River Bridge (now the Benjamin Franklin Bridge) was opened here. This invigorated traffic in the surrounding areas, creating favorable conditions for commerce and far less favorable ones for criminals.

In the late 20th century, a major expressway was built through the heart of the former Tenderloin. Thus, a completely new era began in the life of this district. Its dark past was left behind, and Mayor Blankenburg’s dream of “treating” vice finally became a reality. In the 21st century, nothing here remains to remind us of this neighborhood’s tumultuous history.