Philadelphia has a special connection with electricity, dating back to Benjamin Franklin’s experiments. However, the true electric revolution that permanently transformed the city’s landscape didn’t arrive until the late 19th century. This was the era when cozy gaslights and candles began to give way to the dazzling brightness of Thomas Edison and his competitors.

The story of Philadelphia’s electrification is more than just a tale of stringing wires. It’s an epic saga of technological warfare, the establishment of the first central power plants, and how the City of Brotherly Love became a pioneer in building America’s reliable energy grid. We explore how this transition impacted industry, transportation, and the daily lives of residents, and why the infrastructure laid down back then is still the cornerstone of the modern metropolis on philadelphia-future.com.

The Birth of Light

Philadelphia’s journey to widespread electric power began at exhibitions. In 1876, the city hosted the Centennial International Exhibition, commemorating the 100th anniversary of U.S. independence. It served as a showcase for the latest technologies, notably Alexander Graham Bell’s invention, the telephone. While not directly related to lighting, the event drew attention to the immense potential of electricity as a driving force for progress. During this period, the public began to realize that electric current could deliver far more than simple telegraphic communication.

The Role of William Stanley Jr.

A key figure who defined the trajectory of Philadelphia’s electrical industry was the inventor William Stanley Jr. Stanley was a gifted electrical engineer. He designed one of the city’s very first electrical installations. The innovative work of this electrical researcher caught the attention of George Westinghouse, who was Thomas Edison’s main rival in the so-called “War of the Currents.”

Stanley was a true pioneer in the field of alternating current (AC), which eventually became the dominant global standard. The main advantage of AC power was its scalability. Alternating current allowed energy to be efficiently transported over long distances via high-voltage lines. In contrast, the direct current (DC) system promoted by Edison required far more power plants situated close to the end-users.

Thanks to Stanley’s genius and his work on improving transformers, Philadelphia gained access to a significantly more efficient, safer, and scalable power system. In fact, Stanley helped Westinghouse gain the upper hand in Philadelphia, making the city one of the advanced centers that embraced AC technology.

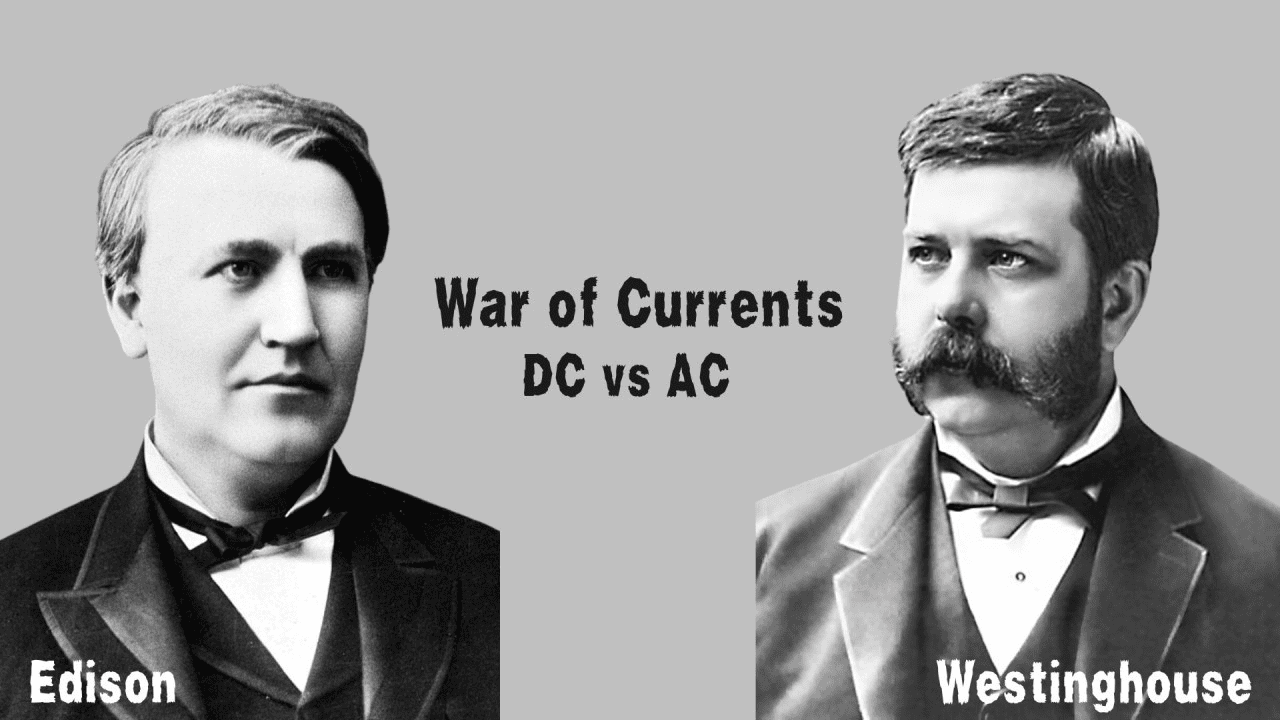

The “War of the Currents” in the City

Philadelphia was no exception to the global standoff between proponents of DC and AC power. In the early 1880s, companies affiliated with Thomas Edison began building the first DC-based systems. These required power plants to be installed close to consumers, limiting coverage to small radii.

In opposition, corporations supporting Westinghouse and Stanley’s technology demonstrated that AC, utilizing transformers, could serve large territories from a single central generating station. This offered a significant economic and logistical advantage, ultimately tipping the scales in favor of the AC system.

The First Public Station and Street Lighting

As in most major cities, the electrification of Philadelphia occurred gradually. Initially, power was supplied to industrial facilities and affluent private homes, often from small, autonomous generators. However, the real breakthrough came with the advent of centralized public generation.

The first powerful electricity-producing enterprises emerged in the late 19th century. They began to power arc lamps, which for the first time filled the streets with bright, albeit harsh, light. This was a turning point that tangibly improved the quality of life for city dwellers.

- Arc lamps replaced kerosene and gas equivalents on main thoroughfares.

- Crime rates decreased thanks to better visibility.

- Citizens gained the ability to move safely after sunset.

- Subsequently, electricity began to power the first streetcars, fundamentally transforming the transportation system.

Long-Term Consequences

The introduction of electricity stimulated a construction boom and economic development. New industries that required powerful machinery gained the necessary energy source. Electric elevators allowed for the construction of high-rise buildings, transforming the architectural landscape of the business district. Power facilitated the emergence of new household appliances, enhancing the quality of life for ordinary residents. Philadelphia became a successful industrial hub that quickly adapted to the latest technological advances.

For a more profound understanding of the evolution of electrification, here are the key events that shaped the city’s energy landscape.

| Sector | Pre-Electrification (Late 19th Century) | Post-Electrification (Early 20th Century) |

| Transportation | Slow horse-drawn streetcars, omnibuses | Fast electric streetcars, subways |

| Lighting | Gas and oil lamps | Bright arc and incandescent light |

| Geography | Population concentration near the center | Decentralization, growth of suburbs |

| Industry | Reliance on steam/water power | Growth of electrotechnical manufacturing |

| Safety | Low visibility at night | Significant improvement in nighttime illumination |

The Legacy of the Current

For Philadelphia, electrification was not just a technological upgrade but a fundamental step toward achieving modern metropolitan status. The city, which became the arena for key battles between Edison’s DC and Westinghouse’s AC, ultimately chose alternating current. This strategic decision, backed by William Stanley Jr.’s innovations in transformers, provided Philadelphia with a long-term advantage.

The implementation of robust systems allowed the city to decentralize industry and residential areas, spurring Philadelphia’s geographical expansion. Electricity also dramatically changed the city’s nightlife, making streets safer and public spaces more accessible. Electrification became the backbone for the development of urban transport—from streetcars to the subway—which, in turn, made Philadelphia more economically dynamic.