Philadelphia, the city that birthed the idea of American freedom, was also the cradle of its transportation evolution. For centuries, while the streets were still paved with cobblestone, the “City of Brotherly Love” sought ways to accelerate its rapid growth—from horse-drawn carriages to underground highways. This iron and electric odyssey is not just a story about laying rails. It is a narrative of how engineering ingenuity and the need for swift movement turned Philadelphia into a true pioneer of American urban mobility. We explore how old horse-drawn streetcars spurred the creation of one of the first subway systems in the U.S., and why Philadelphia’s transit network remains a monumental testament to that era, over at philadelphia-future.com.

The Wheeled Beginning

The history of urban movement in Philadelphia began long before the invention of internal combustion engines. This historic event took place in an era where the main driving force was the muscle energy of horses. In the 1830s, as Philadelphia’s population rapidly grew and city neighborhoods expanded, there arose a pressing need for organized transport. It was then that omnibuses—multi-seat, horse-drawn carriages—began to circulate on the streets.

This means of transport, whose name comes from the Latin word “for all” (omnibus), became the first true form of public transit. Despite the movement being clumsy and relatively slow due to the cobblestones and frequent traffic jams caused by overly narrow streets, it was a necessary step for a large city. Comfort, to put it mildly, left much to be desired. Passengers were seated tightly, and the ride was accompanied by constant shaking. However, the omnibuses were the first to offer a service accessible to the general public, helping people cover significant distances that were previously only manageable by private carriages or required a long walk. This clearly demonstrated how industrial development and city growth shape the demand for organized logistics. The first routes often ran from port areas to commercial centers, connecting key points of business life.

The Iron Artery

The real revolution in urban passenger transport that preceded electricity came with the advent of the horsecars. These were carriages that, like omnibuses, were pulled by animals, but they moved on laid steel rails. This step was a significant breakthrough: the rails substantially reduced rolling resistance, allowing a much larger number of people and goods to be transported faster and, importantly, with less effort for the horses.

The official start of the horsecars era in Philadelphia dates back to 1858, when the first route opened on Fifth Street. The efficiency of the new system was so evident that the network quickly began to expand. By the 1880s, Philadelphia’s horse-powered urban transit network had become one of the largest in the United States, covering most urban areas. This eased logistics for residents and facilitated the further expansion of the city beyond the historic center, as people could live further away from work.

However, even rail transport faced natural challenges, especially on sections with difficult terrain. For example, on steep slopes, such as on Germantown Avenue, it was extremely difficult for horses to pull the cars. To solve this problem, the city experimented with innovative, though short-lived, solutions. This is where cable cars appeared. They operated on the funicular principle: a central power station drove a steel cable hidden beneath the street, and the car, using a special grip, latched onto the cable and moved. This allowed for easy conquering of difficult climbs and descents. Although this technology was eventually supplanted by electricity, it became an important phase in the search for mechanical solutions for urban transport infrastructure.

The Electric Surge

The end of the 19th century brought electricity, which forever changed the face of public transport. In 1892, the first successful electric streetcar line was launched. Within a few years, horses were finally pushed out of the business. Electric streetcars were faster, more reliable, and more environmentally friendly than their equine predecessors. This large-scale modernization led to the consolidation of many small companies under the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT), the predecessor of the city’s modern transit system. This period marked a true boom in urban infrastructure.

To cope with the increasing traffic in the city center, engineers turned to underground solutions. The opening of the Market–Frankford Line (MFL, the “Blue Line”) in 1907 and the Broad Street Line (BSL, the “Orange Line”) in 1928 became a monumental milestone. These were full-fledged subway lines that allowed people to move quickly between distant neighborhoods and the center. These arteries remain the basis of the network even today.

The Birth of SEPTA and an Innovative Future

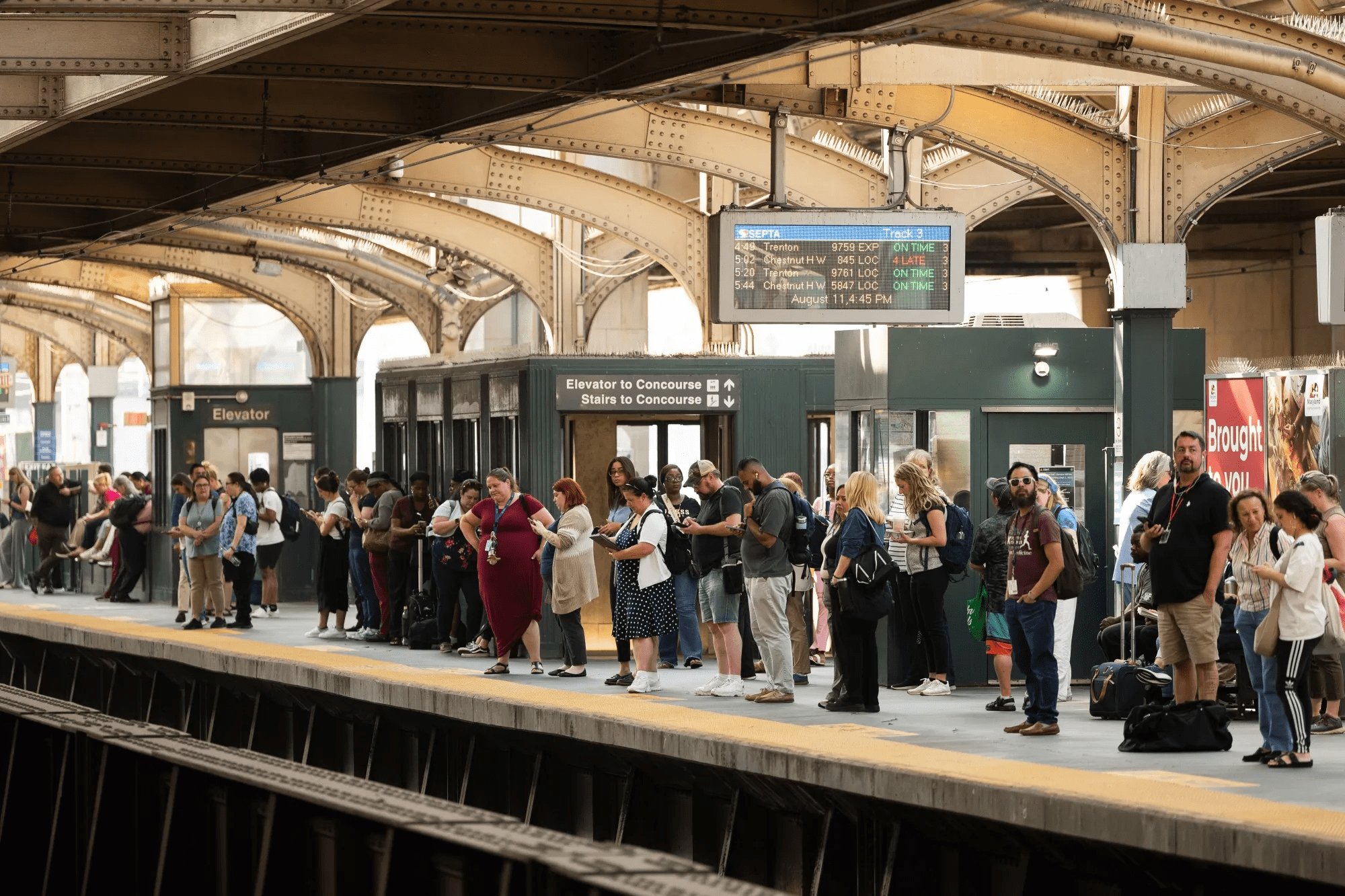

A key transformation took place in 1968. All private and public operators, including the PRT’s successor, were merged and brought under the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA). This body took responsibility for the management and development of all types of urban and suburban passenger service in the region. This ensured more coordinated funding, planning, and integration of bus routes, commuter trains (Regional Rail), and rapid transit lines.

Today, SEPTA continues to work on modernization, facing challenges typical of megacities: the need to fund aging infrastructure and the necessity to reduce the carbon footprint. The transition to more modern, low-floor buses, the renewal of subway rolling stock, and the development of the trolleybus system (routes running on hybrid or fully electric power) demonstrate a commitment to efficiency and environmental sustainability. The implementation of the “Key Card” electronic ticketing system is just one example of how technology is simplifying service usage.

Timeline of Transportation Development

| Era | Main Mode of Transport | Year of First Launch | Key Feature |

| Horse Power | Omnibus | 1830s | First regular service |

| Rail Horse Power | Horsecar | 1858 | Faster and easier movement on rails |

| Electrification | Electric Streetcar | 1892 | Replaced horses, increased speed |

| Underground Transit | Subway (MFL) | 1907 | High-speed long-distance connection |

| Consolidation | SEPTA | 1968 | Centralized management of the entire network |

As the table shows, the city did not merely follow progress; it created it. The transition from the slow, horse-drawn omnibus to complex electric streetcars and finally to the subway was swift.

This electric transformation allowed Philadelphia to become one of the first American metropolises where daily mobility ceased to be a privilege. It shaped the modern urban landscape and, importantly, provided the foundation for the city’s economic dominance in the colonial and post-industrial periods. Today, the extensive SEPTA network is not just a way to get around, but a living, functional monument to this innovative era, constantly recalling the pioneering spirit of the “City of Brotherly Love.”